Liberty Hall c. 1796

While log cabins came to define colonial settlements in Kentucky, more affluent Kentuckians like Senator John Brown preferred a grander type of home. As the elite class built their estates in the new territory, they brought with them the popular Georgian and Federal architecture styles of the Eastern United States and England.

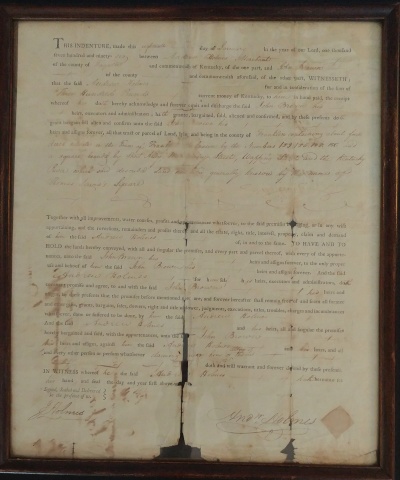

In January of 1796, John Brown bought property in Frankfort— Kentucky’s growing capital city. When construction of Liberty Hall began, it would’ve been one of the grandest homes in town with four acres of land along the banks of the Kentucky River[1]. Prior to Euro-American settlement, this section of the river would’ve been a crossing point for the Shawnee and Cherokee. Aware of this, John created a ferry here giving him control over the waterway.

The building was designed by a Philadelphia architect in the Georgian style, which was very popular at the time[2]. Not everyone was a fan of that style, however, including John Brown’s teacher, mentor, and friend, future President Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson urged his friend to build something more fashionable like that of his own home, Monticello, and drew up a French inspired one-story architectural plan for Liberty Hall. However, by the time John Brown received the letter, a two-story frame had already been constructed. John used small portions of Jefferson’s plans though, like the staircase feature that runs from the back porch to the attic[3].

Liberty Hall, like many other buildings from this period, was made using both free and enslaved labor. We know that one of the enslaved people who would’ve constructed Liberty Hall was 12-year-old Harry Mordecai, who would later become one of Frankfort’s most talented plasterers and bricklayers. He and other enslaved individuals would have plastered and whitewashed the walls and laid the bricks in the unique and time-consuming Flemish pattern[4].

John and his wife, Margaretta, moved into the house over the course of 1800 to 1801 and soon after they planted a catalpa tree that still stands on the grounds today. Elsewhere on the property they created a garden where they would grow fruits, vegetables, and flowers[5]. Despite the family already living there, the home wasn’t completed until 1803. The window glass was the last thing to be added, much to Margaretta’s dismay[6].

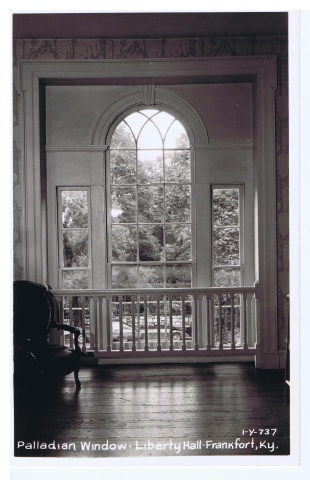

Since its construction, the architecture of Liberty Hall has been widely celebrated and replicated, most notably the Palladian window, which has become a symbol of the site and can be seen throughout downtown Frankfort. In 1980, award-winning author, architectural expert, and historic preservation advocate, Clay Lancaster wrote in A Critique on Liberty Hall:

[Liberty Hall] is one of the finest example[s] of early federal-era architecture in Kentucky. Other early Kentucky buildings display elements of the style, but the refinement and sophistication of Liberty Hall is unparalleled.

It features a pedimented three-bayed central pavilion, whose focus is a beautiful colonnetted doorway with a fine Palladian window superimposed, and having a lunette set in the tympanum of the pediment on axis. The exquisite cornice carries left to right across the entire façade. Above the gabled roof rise a pair of equally balanced and substantial chimneys, capped in the mid-eighteenth century Virginia tradition, and which are unique in Kentucky. The excellent proportions of this façade indicate that the house must have been designed first on paper as an elevation drawing, and was probably the earliest in the commonwealth, at least in the domestic field.

It is most fortunate that Liberty Hall has not been spoiled by a changed environment. The retention of sympathetic surroundings in the city today is a phenomenon. This condition was not achieved at LHHS without considerable effort and expense, as in the purchase and removal of the later house interlaying it and the Orlando Brown House. Thus the visitor enters Liberty Hall receptive of its charms and is agreeably fulfilled. The gardens behind it tie in with the propriety of the setting.

References

[1] Land Transfer. Liberty Hall Collections

[2] Pat Wellington, The Building of “Liberty Hall,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 1971

[3] Thomas Jefferson to John Brown, April 5, 1797, in Thomas Jefferson Papers.

[4] Sharon Cox, Harry Mordecai, Plasterer and Bricklayer of Frankfort, Kentucky, Journal of American Decorative Arts, Volume 42, 2021. https://www.mesdajournal.org/2020/harry-mordecai-plasterer-and-bricklay…

[5] Margaretta Brown to Eliza Quincy 12/22/1804; John Brown to Margaretta Brown 2/6/1811; Margaretta Brown to Orlando Brown 7/7/1819

[6] Margaretta Brown to John Brown Feb 15, 1802. Covington Collection, Louisville