While Dolly spent her life of over 80 years enslaved to the Callaway family, her son Frederick Hart experienced a labyrinthine journey of enslavement to several interrelated families of prominent early Kentucky settlers. Personal and familial connections between the women of the Callaway and Hart families indicate that Frederick’s skills and service may have been shared among these households. Research into the lives and written records of African Americans in the Antebellum period is especially challenging due to few records of detail. The evidence of Frederick’s journey lies within wills and documents among the white family records, as well as traces of his presence among unforeseen calamities reported in newspapers and personal accounts in the interviews of John Filson and Lyman Draper.

After the initial establishment of Fort Boonesborough in 1775, many settlers focused their efforts on improving separate plots of land outside of the stockade, though Colonel Richard Callaway and his family lived in one of the cabins in the Fort. One of Dolly’s responsibilities while living at the Fort was to tend to the young Callaway children, in addition to caring for her own young infant. Captain Nathaniel Hart Sr. spent most of his time overseeing the clearing and planting of land and the building of a log home about a quarter-mile away, on Silver Creek, near present day Red House. Hart and his brother, David Hart, enslaved many men to manage these 640 acres, to fell trees, build structures, grow crops, and to provide defense. Their older brother Colonel Thomas Hart III lived in a blockhouse in the Fort.

Over the next several years, ongoing tensions and confrontations between the white settlers and Indigenous tribes required constant vigilance. Dolly and other enslaved residents of these new settlements would be called upon numerous times to signal alarms, take up arms, build defenses, attend to injuries, and work among the constant threat of danger and death. In July 1776, Chickamauga Cherokee raiders burned N. Hart’s log home and destroyed the apple tree orchard in the days after the infamous Shawnee and Cherokee kidnapping of two of the Callaway’s daughters and one of the Boone’s daughters. Subsequently, N. Hart moved into the Callaway cabin in the Fort for the next several tumultuous years.[1]

In 1778, R. Callaway was elected to represent Kentucky County in the Virginia General Assembly. In October of 1779, the Virginia Legislature granted his petition to build a ferry across the Kentucky River at Fort Boonesborough. On March 8, 1780, he and several companions were working on his ferryboat about a mile above the settlement, when they were fired upon by a party of Shawnee. Callaway was killed, scalped and burned. When his body was recovered, it was noted that the Indians had rolled the body in the mud. Speculation is that he was detested by the Indigenous people. Pemberton Rawlings and one enslaved man were also killed. Two other enslaved men were captured and not heard from again. [2]

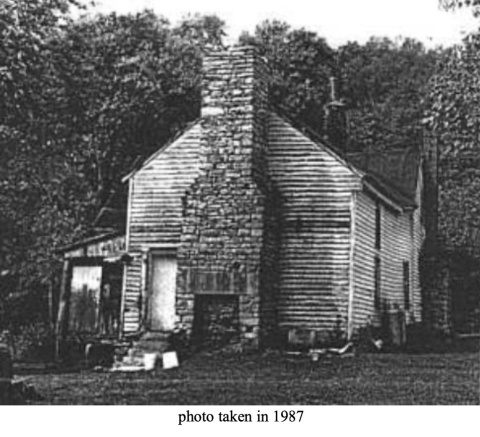

In the fall of 1780, after a few months of relative peace, N. Hart moved his family, cattle, sheep, horse, and enslaved people from North Carolina to his re-built log home which became known as Hart’s Station at White Oak Spring. Other families moved in, bringing the numbers at Hart Station to around one hundred. The Hart’s two-pen dogtrot log home remained standing until 1989. [3]

In the summer of 1781, Callaway’s widow Elizabeth Jones Hoy Callaway, having endured multiple traumatic events and losses, moved to her son Major William Hoy’s home at Hoy Station. She took her young children with her, along with Dolly. But in a cruel twist, it is likely that, before leaving the Fort, Elizabeth sold Frederick to N. Hart, as development of his station was expanding. Despite Frederick’s young age, he would have been assigned duties such as hauling water and materials, while also learning skills from the older enslaved men. After W. Hoy was killed in 1790 by a party of Shawnee, Elizabeth and Dolly moved to the home of Callaway’s daughter, Keziah, wife of Judge James French. Dolly lived into her eighties, as there are multiple accounts of Dolly’s presence at an 1840 ceremony to commemorate the settlement of Boonesborough. Research has not uncovered evidence that she was ever manumitted. It is presumed that she was buried in an unmarked grave in the French family cemetery in present day Montgomery County, where E. Callaway and K. French were also buried. There is scant written record to document the constant personal trauma and stress that Dolly endured during her long life.

In July of 1782, Cherokee raided Hart’s Station, and N. Hart was killed. [4] He was buried in the nearby Lisle cemetery. Hart’s will, drawn up in June of 1782, assigned his wife Sarah Simpson Hart, two eldest sons Simpson and Nathaniel Jr., and his two brothers as executors. [5] Sarah Hart died in 1785, leaving the settling of the Hart estate to N. Hart’s eldest brother Thomas, as the children were too young to serve. He was assisted by Sarah’s son-in-law Isaac Shelby who had married her daughter Susannah Hart. Written accounts tell of young Frederick sent to fetch by horseback the preacher Elkins to officiate this wedding in 1783. [6] Letters archived in the Shelby-Bruen papers reflect a warm, familial relationship between T. Hart and I. Shelby, with discussion of land management, the raising of Nathaniel and Sarah’s youngest children, and the administration of estate affairs. [7] With this close family relationship and given that Thomas had known Frederick since his birth, it seems likely that Thomas either rented or was gifted the young trusted servant Frederick, though no record of this transaction has been uncovered. What does exist is the detail within N. Hart Sr’s will which lists a young slave by the name Frederick. Shelby oversaw the years-long administration of Sarah’s estate, and in 1804 Frederick was listed by first name on the inventory. There is also great detail of the years in between showing that Frederick was rented for income, potentially pointing to a rental to Thomas Hart.

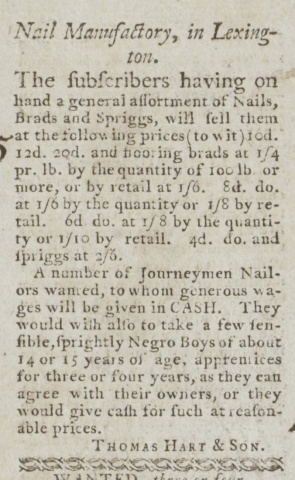

Slavery provided the workforce for the rapidly expanding construction enterprises and subsequent wealth of white land and business owners throughout Kentucky. Over the next many years, T. Hart would expand his lucrative mercantile business, manufacturing rope, cloth, and nails, and in 1794 he established a home and business in Lexington. In October 1794, Thomas Hart & Son placed an ad in the Kentucky Gazette that the company "would wish also to take a few sensible sprightly Negro boys of about 14 or 15 years of age apprentices for three or four years as they can agree with their owners, or they would give cash for each at reasonable prices”. The rapid growth of industry in this urban environment translated to the increasing practice of rental of enslaved people in the central Bluegrass. The clues point to Frederick Hart being an indispensable figure in T. Hart’s growing enterprises. Upon T. Hart’s death in 1808, his son, attorney Nathaniel Gray Smith Hart, would likely have inherited Frederick Hart, along with businesses and other property. The 1810 census shows N. G. S. Hart with 18 enslaved persons in his household, with one person near the same age as Frederick.

Thumbnail: Kentucky Gazette September 9, 1794 - Courtesy of the Lexington Public Library

About the Author:

Rachel Grimes is a composer and pianist based in Kentucky who creates music for chamber ensembles, orchestras, film, multi-media installations, and collaborative live performances. She is a multi-generational Kentuckian interested in how genealogy and history research can lead to social change. She has been a member of African-American Genealogy Group of Kentucky since 2019, and a Board member since 2024. She is a past Board member of the Port William Historical Society, and is a member of the Filson Historical Society, Madison County Historical Society, and the Fort Boonesborough Foundation. www.rachelgrimespiano.com

Sources and Further Reading:

[1] Simpson History by Wanda Snyder

[2] Daniel Bryan interview, Draper MSS 12C 14(18)

[3] Simpson History by Wanda Snyder

[4] ibid.

[5] Lincoln County Will Book A: 4 and A: 93, cited in Harry G. Enoch and Anne Crabb, African Americans at Fort Boonesborough 1775-1784 (2019), p. 85 & 108.

[6] Orlando Brown, “The Governors of Kentucky,” Frankfort Commonwealth, January 10, 1861

[7] Shelby-Bruen papers, Filson Historical Society

Settling Boonesborough by Harry G. Enoch and Anne Crabb

Searching for Boonesborough by Nancy O’Malley

Next: Tracing the Harts - Part 3: Manumission to Self-Determination