In 1840, U. S. Census records reflect that 23% of Kentucky’s population was enslaved. A decade later it decreased to 21.4%. In 1850 Franklin County had 634 enslavers with 3360 people enslaved. There were 358 free people of color, living mostly within Frankfort. Some people who had been enslaved in an urban environment chose to stay nearby and continue to work in their familiar surrounds, sometimes living within yards of their former enslaver.

After Frederick Hart’s arrival at Liberty Hall, he became involved with an enslaved woman named Judith “Judy” Brown. Given the use of the enslaver’s surname, it is likely that Judy had been at the estate for a long time, potentially since birth. Marriages between enslaved people were not legal at the time, though it appears that Frederick and Judy lived together and had at least two children. There was a significant age difference, with Frederick approximately thirty years Judy’s senior. Narratives and letters indicate that Frederick Hart was a strong, able-bodied man into his eighties. The 1850 U. S. Census lists Frederick Hart as 70, and Judy as 40, and daughter Sarah Jane as 16. All were listed as “mulatto,” a term indicating biracial heritage. Records reveal that at that time, Frederick was free, and Judy and Sarah Jane were still enslaved.

Economic and racial tensions had been increasing throughout Kentucky during the 1830s and 40s, and wealthy enslavers took extra steps to ensure that free people were monitored, in part to dissuade alliances between free people and enslaved freedom-seekers. The “List of Free Negroes Taken by the Trustees of Frankfort July 16, 1842,”[1] of which Orlando Brown was a trustee, endeavored to create a census of all the free people of color living and working in Frankfort. The original document listed Frederick Hart working as a farmer, with no property, aged 65, standing indicated with a “G”, for good. Orlando's records reflect that Frederick Hart had worked as a carriage driver for him. Hart was likely also involved in various household tasks and maintaining the extensive gardens behind Orlando Brown house and Liberty Hall. Hart likely stayed in Frankfort, even after his manumission, in order to remain with Judy and their two children, Sarah Jane and Henry until their manumission debt was paid.

Kentucky enslavers granted freedom to enslaved workers based on a variety of rationales: moral grounds, the enslaved person had reached a certain age, or as a result of an estate requirement. Others offered freedom through manumission, as a contract of sorts. Often there was a dollar amount to be paid to the enslaver by the enslaved, along with paperwork to be signed. In some cases, free people purchased their own family members. Despite being enslaved, some people were able to retain a portion of their wages earned as a result of being hired out or for having taken extra work. Therefore, it was possible in some cases for a person to earn enough in savings over several years to pay their own manumission debt.

While no paperwork for Frederick Hart’s manumission exists within the Orlando Brown archives, there is circumstantial evidence that it occurred in the mid to late 1830s, likely after the time of the settlement of the brothers James Brown and John Brown’s estates in 1835. There are indications that Frederick Hart had been inherited by James and Nancy Brown from the estate of her brother, Captain N.G.S. Hart. Given the close-knit nature of the Hart, Shelby, Clay, and Brown families during the early 1800s, there may not have been official paperwork for every transaction among family.

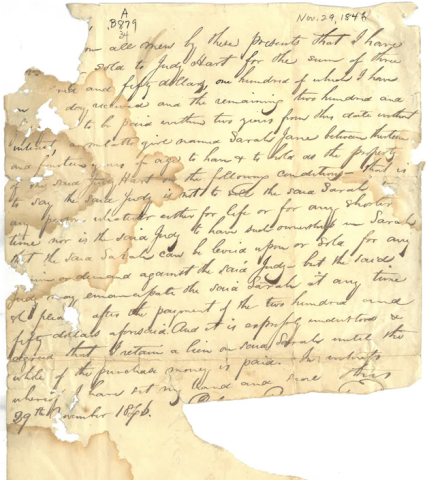

Striking primary evidence does exist however for the manumission of Judy Brown and her daughter Sarah Jane. The Orlando Brown papers at the Filson Historical Society contain a bill of sale document dated Nov. 29, 1846[2] between Orlando Brown and Judith Brown detailing the sale of “a mulatto girl named Sarah Jane between thirteen and fourteen years of age” to her mother Judy for $350. The document indicates that Judy had already paid $100 of the balance at the time of this agreement.

This stunning evidence reveals an extremely rare situation during the time of slavery in the U. S. - that of an enslaved woman paying the manumission debt of both herself and her child. Judy continued to pay down this debt. A letter from the Liberty Hall archives dated Frankfort, KY May 19, 1850[3] from an Kentucky Attorney General James Harlan to Col. Orlando Brown reads:

Dear Sir,

Judy has called on me for advice in relation to the emancipation of herself and daughter Sarah. By the provisions of the New Constitution all persons emancipated after it goes into effect must either leave the State and [or] be sent to the Penitentiary. The Convention meets the 3rd June to proclaim the New Constitution as the supreme law of the land; and it is necessary that something should be done for [?] in the cases of Judy and her daughter. Judy says she has paid you in full for herself, but still owes you $100 for Sarah – I believe Frederick could secure the Payment of the balance. If that would be satisfactory, prepare deeds for Judy & Sarah Jane and enclose them to me on the Receipt of this. I will arrange the matter with Frederick before I deliver the papers.

Col. Orlando Brown Washington City

Very Respy & truly Your friend

J. Harlan

You need not have any Official Certificate to the papers. Your hand writing is well known here. JH

In 1850, Orlando Brown was serving as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, under President Zachary Taylor. In that role he supervised assimilation and manual labor schools for indigenous people. Brown resigned from this position later in the year, but while he was away, his legal affairs were being handled by James Harlan. Notable in this letter is the indication that Judy has paid her own debt in full, and the bulk of the debt for Sarah Jane. Also notable, is the reference that Frederick could provide the balance, indicating he was still in Frankfort, free, and earning income.

While the 1850 U. S. Census did list Frederick, Judy, and Sarah Jane, there was no mention of Henry. Henry Hart’s death certificate lists his birth year as 1839 in Frankfort KY. No manumission documents have been uncovered for him. Potentially Henry was already living in northern Ohio, receiving an education and musical training.

Given the increasingly hostile environment for African Americans created by the new Kentucky laws, there was great incentive to leave Kentucky for a new life in freedom. Many enslaved and free people started leaving the state northwards via the riverways. With Liberty Hall being situated on the banks of the Kentucky River, it is likely that the Harts travelled by riverboat in 1853 towards the northern KY counties or straight to the Ohio River, routes often used by people traveling via the Underground Railroad.

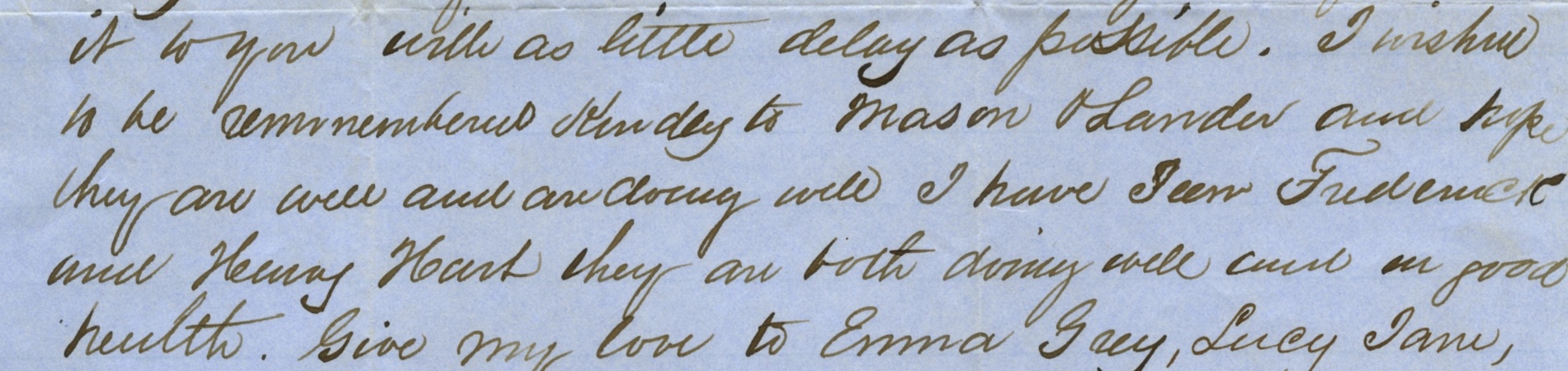

A crucial source of evidence in the Hart family story, is a letter dated March 8th, 1854, from Robert Brown addressed to Mr. Lander Brown, Frankfort, Kentucky. The tone of the letter is a jarring combination of cheerful information, grave worries, and delicate negotiation. Robert Brown, writing from the resettlement town of Chatham, Canada, had formerly been enslaved at Liberty Hall, and addressed the letter within to an enslaved friend named Willie. Robert updates Willie on his settlement in Chatham and his good health, then mentions that he is aware that Willie had been sold to Harry Todd, and is worried that there has been no news. He then addresses Orlando Brown asking him to forward the letter to Willie along with an offer to purchase his wife and child for $750. Within the updates, Robert mentions that he “has seen Frederick and Henry Hart. They are both doing well and in good health.[4]”

On July 29, 1859, the Cleveland Daily Leader published a brief article on Frederick Hart, as a part of a series of historical recollections from area community members that read:

Frederick Hart, an old colored man, about 100 years old, presented as the first child (other than Indian) born in Kentucky. He was either a slave of Daniel Boone or one of his associates, and was manumitted about twenty years ago. He now resides in Columbia, and appears like an honest, intelligent, but very infirm old man.

The 1860 U. S. Census reflects that the Harts settled in northern Ohio, in Lorain Co. near Columbia Station. Perhaps Robert Brown had visited the Harts on his journey north to Canada, crossing Lake Erie near Sandusky, just down the road from Columbia Station. Frederick Hart is buried there in the oldest section of the the Columbia Township Cemetery, having died on October 24, 1865, nearly 90 years old.

Thumbnail: Mss. A B879 38 | Orlando Brown Papers, Robert Brown Letter, 1852. The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, KY

About the Author:

Rachel Grimes is a composer and pianist based in Kentucky who creates music for chamber ensembles, orchestras, film, multi-media installations, and collaborative live performances. She is a multi-generational Kentuckian interested in how genealogy and history research can lead to social change. She has been a member of African-American Genealogy Group of Kentucky since 2019, and a Board member since 2024. She is a past Board member of the Port William Historical Society, and is a member of the Filson Historical Society, Madison County Historical Society, and the Fort Boonesborough Foundation. www.rachelgrimespiano.com

Sources and Further Reading:

[1] List of Free Negroes Taken by the Trustees of Frankfort July 16, 1842. Orlando Brown Papers. The Filson Historical Society. Louisville, KY.

[2] Bill of Sale Sarah Jane 1846. Mss A B879 34. Orlando Brown Papers. The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, KY

[3] James Harlan to Orlando Brown. May 19,1850. Transcription from original document, provided by Vicky Middleswarth. Liberty Hall Historic Site, Frankfort KY

[4] Robert Brown letter, 1852. Mss. A B879 38. Orlando Brown Papers. The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, KY