Frederick and Judy Hart lived the remainder of their lives in freedom in Lorain County, in northern Ohio. Unlike other Americans who remained oppressed by the system of slavery, the Harts had procured their own manumission and that of their children, a process not accessible to most enslaved people. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 marked a significant increase in fear and terror among enslaved and free Blacks in and around the border states. Heavy penalties and possible imprisonment were issued against anyone assisting freedom seekers. Despite the potential consequences, many Americans in the area of Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana continued to assist people who were traveling north to escape enslavement. Ohio State University professor Wilbur Seibert’s 1898 book “The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom” demonstrates in great detail the resolute efforts of so many people to provide safe passage[1]. Many routes leaving Kentucky utilized creeks and waterways to access small boats along the Ohio River for crossing to the banks of southern Indiana or Ohio. Arrival destinations such as Madison and Rising Sun in Indiana, and Cincinnati and Ripley in Ohio led further north, often to departure points leading to Canada.

The 1860 U. S. Federal Census lists Frederick and Judy Hart living in Columbia Station, Lorain Co. OH, along with a young woman named Mary, age 19 [2]. Apparently Mary was their youngest child, though there is no further evidence of her in any records uncovered thus far. The proximity of Columbia Station to the southern coast of Lake Erie and the crossing routes to Canada at Sandusky and Cleveland, as well as frequented North/South routes along the Underground Railroad, points to their possible participation in aiding freedom seekers. The Harts’ deep knowledge of Kentucky’s enslaver families and society, personal relationships with free people in Frankfort, as well as their income-earning status may have helped provide additional resources for these efforts.

Likely around this same time, the Harts’ son, Henry, was working as a barber and musician on the riverboats along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. At some point in the early 1860s, he took up residence in New Orleans, LA. Along the way, he met the young pianist Sarah Frances Smith from Jeffersonville, IN. By 1865 they were both employed as performers at the Prescott Museum. Sarah’s mother Angeline Mason Smith had been born into slavery, enslaved by James Murray Mason, a U. S. Senator from Virginia, who introduced the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 [3]. In March of 1861, Mason withdrew from the Senate and joined the secessionist movement of the Confederate States [4].

Henry Hart may have returned to Columbia Station, OH for a short while after the death of his father during the fall of 1865. No other Hart family members are buried at the Columbia Township Cemetery, which may indicate that they moved after Frederick’s death. Given the end of the Civil War, potentially Judy and Mary moved with Henry back to New Orleans. At some point in 1866, Henry and Sarah were married. Not long after, in October of 1866, Sarah gave birth to their first child, Estella. Perhaps due to the responsibilities of family life, the Harts, along with Sarah’s mother, moved to Evansville, IN, a busy port town also situated along the Ohio River. Henry continued to work on steam packet boats for years to come. According to a brief article on March 31, 1875 in the Evansville Journal, Sarah’s mother Angeline Mason Smith Seldon had worked as a stewardess on riverboats for many years [3]. At the time of her death in 1875 Angeline was employed on the luxurious Robert E. Lee steamboat, built by Howard Ship Yards in New Albany, IN, in 1866 [5].

The Reconstruction period initially offered optimism and energy for young Black entrepreneurs. Many newly-emancipated people bought property, started businesses, and ran for political office. As this momentum built during the late 1860s and early 1870s, many Black musicians struck out on their own, breaking ties with white-owned touring groups that relied on the immense popularity of burnt-cork minstrel acts accompanied by nostalgic plantation tunes that played on racist tropes.

By June of 1870, the Harts had purchased their residence in Evansville, IN, and Henry was running a barber shop between trips along the Ohio River [6]. Their second child, Lilian, was born in the fall of 1870, and died soon thereafter. Daisy was born in 1872, William (a girl known as Willie) in 1875, and Myrtle in 1877. While it was a very busy time for Sarah Hart, there is evidence within the initial sheet music publications to suggest that she played a vital role in transcribing and arranging Henry’s tunes for piano for official publication. Henry was known as a violinist, songwriter, and bandleader. None of the newspaper articles over the years ever suggest he sat down at the piano, though many of his daughters did. It would seem that Sarah taught all the girls the rudiments of piano technique, juggling their care and education while Henry travelled to great acclaim along the riverways.

During the 1870s, Hart travelled the region with his ensemble, known as Henry Hart’s Original Colored Minstrels. He collaborated with many musical artists including the singer Sam Lucas and banjo player Jake Hamilton, as well as other popular touring groups like Callender’s Original Georgia Minstrels. Several of Hart’s published works were commissions for individuals, noted in the dedications on the covers.

“Those Charming Feet”, originally published in 1870 by Kunkel Brothers, St. Louis, MO, was labeled a “Song and Dance”. This parlor tune was made popular by Irish-American minstrel entertainer Billy Emerson, who appears on the cover. Emerson performed in blackface with the Kunkel Nightingale Minstrels between 1864 and 1867. Known for his genteel style of song and dance, he formed Emerson and Manning’s Minstrels, which spent time in Cincinnati, Ohio, and nearby Covington, Kentucky, between 1869 and 1870. It is likely that Henry Hart, known around the region, would have been introduced to Emerson during this time.

Hart’s solo piano piece “Idlewild Mazurka” was published in 1871 and dedicated to Captain Gus Fowler, who led the U.S. Mail Idlewild side-wheel packet boat on the Ohio River between Cairo, IL, and Evansville, IN. Hart worked as a barber and musician on this boat, which was built in Jeffersonville, IN, by the Howard Ship Yards and operated from 1870 to 1881.

Hart would publish many more pieces with American music publishers throughout the 1870s, including “Daffney Do You Love Me”, “Gipsey Queen Waltzes”, “C’yarve Dat Possum”, “Evansville Favorite Waltz”, “7:30 - 11 Galop”, “On the Beautiful Lake Erie Waltzes”, and “Good Sweet Ham”. Over the years, the Harts raised seven daughters, all musically trained by their parents on piano, viola, cello, cornet, harp, xylophone, and drums.

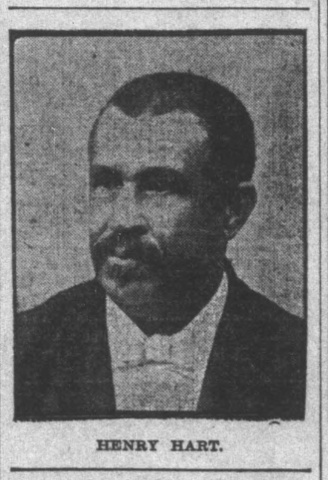

Perhaps due to increasing challenges as a result of the Jim Crow laws being put into place, the family moved to Indianapolis, IN, in 1879, where “Professor Hart and his Orchestra” became a popular dance band choice for upper class hosts, such as Colonel Eli Lilly. Hart’s daughters often joined the band, with Myrtle on harp, Hazel on piano, Clothilde on the drum, and Willie on cello. His dance band was a popular fixture at the area whites-only summer resorts such as West Baden, Wawasee, Harbor Point, and Maxinkuckee.

In the article “A Social Necessity: Henry Hart and His Family of Musicians Always in Demand” in the Sat. April 6th, 1901 edition of the Indianapolis News it is noted:

“What Mr. Hart doesn't know about Indianapolis society is not at all worth knowing. He is on the most friendly terms with the prominent people of the Hoosier capital. He played for Governors Williams, Porter and Mount, and for the inaugurals of Governors Gray and Hovey. He provided the music for the inaugural ball given by Governor Durbin, at Tomlinson Hall, in January. Hart was engaged for the opening receptions of the Columbia Club, the Country Club, the Commercial Club, the Canoe Club, the Propylæum, the Brenneke Academy, the Americus Club and the University Club. He was the musician to furnish music on the occasion of the visits of President Rutherford B. Hayes, President Grover Cleveland, and President Benjamin Harrison.” [7]

To become the most in-demand entertainer for the blue-bloods of Gilded Age Indianapolis is quite notable for a man born enslaved in Kentucky. The Hart family thrived in this growing metropolis, owning multiple properties, and sharing their music gifts for generations. Several of the Hart daughters went on to become teachers and administrators in the public school system.

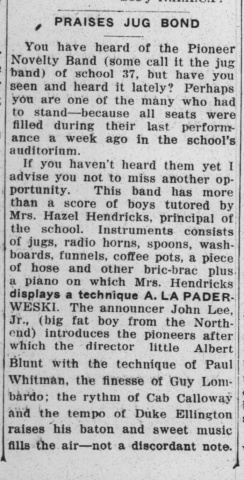

Hazel Hart Hendricks was a violinist, pianist, and a greatly admired principal for Indianapolis Public School #37, a school that was later named after her. To help raise morale at the Colored Orphans Home located near the school, she led a musical ensemble for young boys called the Pioneer Novelty Band. Very popular at community events, the boys sang and played jugs, spoons, washboards and coffee pots while Mrs. Hendricks directed from the piano [8].

Harpist and pianist Myrtle Hart was described in the Chicago Daily News on July 23, 1895 as “…the only colored harpist in the world.” The article described her solo recital performance as “.. marked by brilliant execution, pure tones, and extreme delicacy of touch.” [9]

In Chicago, Myrtle studied harp for three years under Edmund Schuëcker, the first harpist for the Chicago Symphony. She and her father toured together by train along the east coast and her recitals were written about with great acclaim in papers such as The Colored American and the Boston Globe. In the 1920’s, Myrtle adopted the stage name of Louise Kavanaugh and passed as white in order to play in east coast white orchestras, such as the Metropolitan Opera of New York. After divorcing her first husband John Fry, in 1926 she married the white orchestra conductor William MacKinlay and they moved to Boston where he was the music director of the Boston Colonial Theater. Working together in the house orchestra, the Boston Colonial Theater premiered many notable musical works over the next many years. Myrtle also performed with the Ziegfeld Follies and was part of the original motion picture soundtrack recording of the 1936 film “The Great Ziegfeld”.

As the U. S. A. celebrates the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the history and stories of American people are being shared with new focus. African-American founding mothers and fathers were denied their rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Slavery was a foundational practice for the westward expansion of the United States. In Kentucky, it provided the basis for wealth building to many white men who, because of their military service, received sizable land grants. In 1790, enslaved people comprised 16.9% of Kentucky’s population, a percentage which reached 24% by 1840. It is difficult to comprehend how many family stories have been lost due to ongoing oppression and lack of records.

250 years ago, Frederick Hart was born to Dolly, one of two women on an expedition initiated by the Transylvania Company and led by the hired trail cutter Daniel Boone. Dolly was the first African American woman to live in Kentucky and made a significant contribution to the settlement of Fort Boonesborough. Frederick was the first child born in this fort in November 1775. During his years of enslavement, he served many of the wealthiest families in Kentucky. He served in the War of 1812, and later along with the efforts of his wife Judy, provided permanent freedom to their children. Their children, grandchildren, and many generations since have had the opportunity of a life of liberty, the essence of what we celebrate in that Declaration.

Thumbnail: Three sheet music covers of Henry Hart's compositions. Courtesy of Rachel Grimes.

About the Author:

Rachel Grimes is a composer and pianist based in Kentucky who creates music for chamber ensembles, orchestras, film, multi-media installations, and collaborative live performances. She is a multi-generational Kentuckian interested in how genealogy and history research can lead to social change. She has been a member of African-American Genealogy Group of Kentucky since 2019, and a Board member since 2024. She is a past Board member of the Port William Historical Society, and is a member of the Filson Historical Society, Madison County Historical Society, and the Fort Boonesborough Foundation. www.rachelgrimespiano.com

Sources and Further Reading:

[1] “The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom” Wilbur H. Seibert, MacMillan Co.1898

[2] 1860 U. S. Federal Census

[3] Evansville Journal, March 31, 1874

[4] U. S. Senate, A Featured Biography, www.senate.gov

[5] Discover Indiana History, “The Robert E. Lee Steamboat”, by By Ashley Slavey, Megan Simms, Wes Cunningham, Eric Brumfield, & Katy Morrison

[6] 1870 U. S. Federal Census

[7] The Indianapolis News, Saturday, April 6, 1901 “A Social Necessity:Henry Hart and His Family of Musicians Always in Demand” within “Henry Hart and His Family Orchestra (Including Eli Lilly's Recollections)” by Dr. Clark Kimberling, 2007 https://faculty.evansville.edu/ck6/bstud/Supplement1.html

[8] Indianapolis Recorder, May 25, 1935

[9] Chicago Daily News, July 23, 1895